FEDERAL DRUG CASES: DETERMINING A DEFENDANT’S DRUG QUANTITY

In federal drug cases, the most important factors that affect a defendant’s likely sentence are the type of drug and the quantity of the drug for which the defendant is considered responsible. As a federal criminal defense lawyer in the Northern District of Texas (Dallas and Fort Worth), and the Eastern District of Texas (Plano and Sherman), I get lots of questions from clients and their loved ones about how judges determine the defendant’s drug quantity. This article will address some of the most important issues and the most frequent questions I get about drug quantity.

Can Someone Be Responsible For More Quantity Than The Amount Of The Crime?

The federal drug crime statutes generally include a drug quantity. For example, a person could be convicted of the crime of possession with intent to distribute 50 grams or more of a mixture and substance containing methamphetamine. This crime means that the person possessed with intent to distribute at least 50 grams. If you are convicted under this statute, the minimum prison term is five years,[1] and the maximum prison term is 40 years. See 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1)(B). If you plead guilty to this crime, does that mean that your drug quantity, for sentencing purposes, is 50 grams? The answer is, “No.” I explain why, below.

For first-time offenders, in cases where serious bodily injury or death does not result, here are the crimes and punishment ranges for a mixture and substance containing methamphetamine:[2]

Crime: Amount of Mixture

And Substance Containing Meth Punishment Range

Detectible amount or more 0-20 years

50 grams or more 5-40 years

500 grams or more 10 years to life

The crime tells you only the amount needed for a conviction and what the punishment range is. It does not tell you where, within that range, the judge will sentence you. It also does not tell you the quantity of the drug for which you will be considered responsible under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. An example may help to explain these concepts.

Let’s say you are charged possession with intent to distribute with 50 grams or more. For a conviction, the Government would have to prove at trial, beyond a reasonable doubt, that you possessed with intent to distribute at least 50 grams of a mixture and substance containing meth. If you are found guilty, a judge would decide your sentence, and the punishment range would be 5-40 years.

Now, let’s say that, at trial, the Government proves beyond a reasonable doubt that you possessed with intent to distribute one kilo (1000 grams). That is more than the 50 grams the Government needed to prove, so you would be found guilty. The same would be true if the Government proved beyond a reasonable doubt that you possessed with intent to distribute 100 kilos (100,000 grams). That is more than the 50 grams that the Government needed to prove, so, you would be found guilty. In both cases, the punishment range is 5-40 years. When the judge is considering what sentence to give you, the law allows the judge to consider what you actually did and to give you a longer sentence if your quantity is 100 kilos than if it is 1 kilo.

Similarly, if you plead guilty to the crime of possessing with intent to distribute 50 grams or more, you would be admitting that you possessed with intent to distribute at least 50 grams. That means your punishment range is 5-40 years, but again, the judge can consider the actual amount for which you are responsible when deciding what sentence to give you between 5-40 years. This allows a judge to sentence someone whose quantity is only 1 kilo to less than someone whose quantity is 100 kilos, which is fair.

This example explains why the crime amount is different from the drug amount for purposes of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. The crime amount tells you what the Government must prove for a conviction and what the punishment range will be. The Sentencing Guidelines amount is the true amount for which the law considers someone responsible, and it is used to determine what someone’s Sentencing Guideline range will be.

Can Someone Be Responsible For More Drugs Than What They Are “Caught With”?

I am often asked whether someone can be responsible for more drugs than what they had when they were caught or more than what law enforcement found when they executed a search warrant. The answer is, “Yes.” In fact, this happens a lot in federal drug cases. There are many different situations in which this can happen. Below, I describe some of the most common ones.

Responsibility Based On a Person’s Role.

In drug organizations, or even individual transactions, multiple people can be involved, and they may have very different roles. Some roles may make a person responsible for the transaction or the quantity, even though that role never involved touching, or even seeing, the drugs.

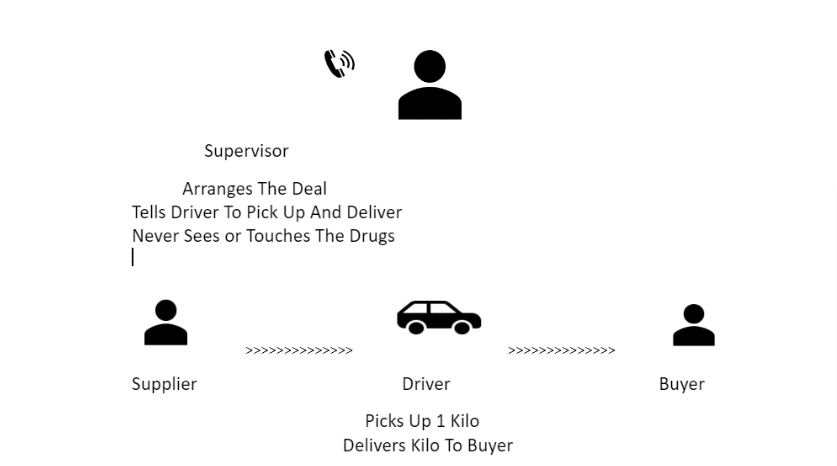

Here is an example. Let’s say a Supervisor in a drug organizations finds out that a Buyer wants a kilo of drugs and will pay a certain amount for the kilo. The Supervisor then contacts a Supplier, who is willing to sell a kilo for less than what the Buyer will pay. This means that the Supervisor can make a profit from buying a kilo from the Supplier and selling it to the Buyer. The Supervisor then arranges a purchase from the Supplier and a sale to the Buyer. Of course, the Supervisor does not want the Buyer to know who the Supplier is, because then, the Buyer could go directly to the Supplier and cut out the Supervisor. So, the Supervisor sends a Driver to pick up the kilo from the Supplier and to deliver it to the Buyer. Here is a diagram showing how this would work:

Figure 1

In this example, the Driver sees and touches the kilo of drugs. Because of his role, the Supervisor never touches or lays eyes on the kilo of drugs and never even gets near it. Does that mean that only the Driver should be responsible for the kilo of drugs, and the Supervisor should not be responsible for zero? Of course not. The Supervisor made the whole transaction possible and directed how it would happen. The supervisor will also, undoubtedly, make more money from it than the Driver. The Supervisor and the Driver had different roles, but as far as quantity, both of them are responsible for one kilo of drugs, even though the Supervisor was never “caught with” anything.

Evidence of Quantity Without Actual Seizure of Drugs.

There are many situations in which defendants can be held responsible for a drug quantity, even if the drugs themselves were never seized or found. These generally involve evidence that a drug transaction occurred. For example, a wiretap may show that two or more people were involved in a drug transaction, even if law enforcement did not intercept the drugs.

Here is an example of what a wiretap might show:

CALLER: Are you ready with the three roosters?

CALLED PARTY: Yes. My man is on the way to you now.

CALLER: He just arrived. The roosters are good quality. My customers will like them. 14 is a good price. Let me know when you have more. Thank you.

In this example, “roosters” is obviously code for drugs. Three roosters means three kilos. 14 means $14,000.00. In context, it may be obvious that “roosters” refers to a certain type of drugs. There may be evidence that these two people dealt exclusively in a certain type of drugs, and $14,000.00 for three kilos may be consistent with the current market price of that drug, as opposed to other types of drugs.

Based on this evidence, a defendant shown to be the CALLER or the CALLED PARTY could be responsible for three kilos of that type of drug.

Another type of evidence that can be used to show a person’s drug quantity is the statement of a witness. This can include statements by the defendant or other people involved in the drug dealing who are cooperating with the Government.

Sometimes, for example, a defendant who is arrested will tell Government agents about other transactions that were unknown to the Government. If a defendant tells agents about how he did a six-kilo deal a month ago, the defendant can be responsible for that six kilos for sentencing purposes. The same could also be true if another arrested person tells the Government that he did a six-kilo deal with the defendant.

Estimates of the Defendant’s Quantity.

For sentencing, the Sentencing Guidelines allow estimates of the drug quantity for which a person is responsible. See U.S.S.G. §2D1.1, comt. n.5; see United States v. Alford, 142 F.3d 825, 832 (5th Cir. 1998). This means that a defendant’s drug quantity can be based on another person’s estimate of the number of transactions with the defendant. For example, a person who is arrested might tell the Government that he had done eight to ten transactions of one kilo each with the defendant. This would mean an estimated quantity of eight to ten kilos.

Does a judge have to accept whatever another drug trafficker says about a defendant’s quantity? No, but for Sentencing Guidelines purposes, proof of drug quantity only requires proof that the quantity is more likely than not. The burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt does not apply to drug quantity for Sentencing Guideline purposes. This means, as a practical matter, that if the Government believes the person, most judges will accept the estimate unless there are facts that at least call the estimate into question. Below, I discuss a recent example of a situation like that.

Conversion of Seized Cash Into Drugs.

Another way that a person can be responsible for unseized drugs at sentencing is when law enforcement finds a large amount of cash, and it is considered drug proceeds and converted into a drug quantity based on the market price of the drug. A court can do this if it finds that the cash was drug proceeds by a preponderance of the relevant and sufficiently reliable evidence. See United States v. Betancourt, 422 F.3d 240, 247 (5th Cir. 2005).

For example, in United States v. Barry, 978 F.3d 214 (5th Cir. 2020), law enforcement executed a search warrant and found methamphetamine and $14,658.00 in cash. The cash was converted, for sentencing purposes, into 852.2 grams of 100 percent pure methamphetamine (a rate of $17,204.23 per kilo). That 852.2 grams was added to the meth found during the search, for a total of 1023.5 grams. The Fifth Circuit upheld the district court’s conversion of the cash into drugs. See id. at 219.

Can a Person’s Drug Quantity Include Someone Else’s Drug Deals?

In federal drug cases, there are usually several defendants. In these cases, it is common for one defendant’s drug quantity to include drugs distributed by other defendants. How is this possible? The typical reason is because of the defendant’s role in a drug trafficking organization.

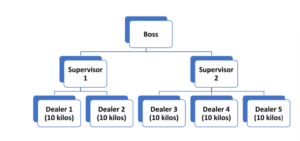

Here is an example of an organization with a Boss at the top, two Supervisors in the middle, and five Dealers at the bottom. Each Dealer does drug deals that total 10 kilos.

DRUG RESPONSIBILITY CHART EXAMPLE

Figure 2

In this example, the quantities for each individual are:

Dealers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5: Each responsible for their own 10 kilos.

Supervisor 1: Responsible for the quantities of Dealers 1 and 2—20 kilos.

Supervisor 2: Responsible for the quantities of Dealers 3, 4, and 5—30 kilos

Boss: Responsible for all quantities—50 kilos

This example illustrates how some defendants can be responsible for the drug dealing of others.

What Rules Apply To Determining Someone’s Drug Quantity?

Under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, a defendant is responsible not just for drugs that are directly involved in the offense of conviction, but for all drugs that are within the scope of the defendant’s “relevant conduct.” Section 1B1.3 of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines defines “relevant conduct.” It includes (i) in a jointly undertaken criminal activity, “all quantities of [drugs] that were involved in transactions carried out by other participants, if those transactions were within the scope of, and in furtherance of, the jointly undertaken criminal activity and were reasonably foreseeable in connection with that criminal activity,” and (ii) any other amounts outside the offense of conviction in which the defendant was directly involved as “part of the same course of conduct or common scheme or plan.” U.S.S.G. §§ 1B1.3(a)(1)(B); 1B1.3(a)(2).

In drug cases, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers cases from Texas, has “broadly defined what constitutes ‘the same course of conduct’ or ‘common scheme or plan.’” United States v. Barfield, 941 F.3d 757, 763 (5th Cir. 2019) (quoting United States v. Bryant, 991 F.2d 171, 177 (5th Cir. 1993). Courts in the Fifth Circuit look to “the degree of similarity of the offenses, the regularity (repetitions) of the offenses, and the time interval between the offenses.” United States v. Rhine, 583 F.3d 878, 886 (5th Cir. 2009).

Importantly, a defendant’s relevant conduct is limited by the scope of the defendant’s “agreement” to participate in the jointly-undertaken activities. According to the application notes to the Sentencing Guidelines:

[T]he accountability of the defendant for the acts of others is limited by the scope of his or her agreement to jointly undertake the particular criminal activity. Acts of others that were not within the scope of the defendant’s agreement, even if those acts were known or reasonably foreseeable to the defendant, are not relevant conduct….

U.S.S.G § 1B1.3, App. Note 3(B).

In general, the scope of a defendant’s “agreement” includes what the defendant agreed to do himself or herself, the activities of others over which the defendant had supervision or authority, and the activities the defendant agreed to assist.

If all of this sounds complicated, it is because it is. Each situation is fact-specific, the legal concepts are not well-delineated, and it really takes an experienced federal criminal defense lawyer to sort it out.

What Defenses Are There For A Person’s Drug Quantity?

Each federal drug case will have its own unique facts. Determining any defendant’s drug quantity will require applying the law, which is complicated, as explained above, to those unique facts. However, there are a number of arguments that can be used to try to persuade a judge that a defendant’s drug quantity should be less than what the Government claims.

Drugs Outside the Scope of the Defendant’s Agreement.

Drug cases sometimes involve overlapping drug trafficking organizations. One individual might belong to two different organizations, but the rest of the two organizations might be separate. It may be possible to show that a defendant is not part of both organizations and should not be responsible for the drug quantities of both organizations.

Quantity Estimate is Wrong or Unreliable.

Although the Sentencing Guidelines allow judges to consider estimates of a person’s drug quantity, an estimate may be wrong or unreliable. Defense counsel can make this argument to try to reduce the defendant’s drug quantity. For example, in a recent case, a cooperating witness claimed that my client sold him a certain quantity of fentanyl pills every month during a twelve-month period of time. Using text messages, I was able to show, however, that the cooperator had only just met my client at the time he made the claim, so that it was not possible that he had bought fentanyl pills for a year.

Wrong Type of Drug.

Sometimes, law enforcement will make assumptions about the type of drug involved in a transaction that they see reflected in a wiretapped conversation or in a text message. When talking or texting, drug traffickers usually use code words for drugs, like “license plates,” “dolls,” or “roosters.” Code words like these are usually dead giveaways that the communication is about illegal drugs, but sometimes, it is not clear what kind.

The type of drug can be very important, because different drugs are punished more severely than others. According to the Sentencing Guidelines, Methamphetamine, for example, is punished much more harshly than heroin or cocaine. If the Government claims that a communication refers to a particular type of drug, but the communication itself is unclear, it may be possible to argue successfully that the communication refers to a type of drug that is punished less severely.

Defendant’s Alleged Role is Overstated.

As I explained above, a defendant who supervises or assists others in conducting drug transactions may be responsible for the drug quantities from the transactions of those other people. If the Government tries to attribute the drug quantities of others to my client based on what they claim to be my client’s role in an organization, I will carefully review the facts to determine whether they have characterized my client’s role accurately. If my client did not supervise or assist particular individuals, for example, there may be a good argument that my client should not be responsible for their drug quantities.

Cash Should Not Be Converted Into Drugs.

If the Government claims cash should be converted into drugs, there are two general types of arguments that can undercut their position. First, a defendant can argue that the cash does not represent drug proceeds. It may be possible to use documents to show that the cash came from a legitimate source. For example, bank records may show that the cash was withdrawn from the bank and that the money going into the account all came from a person’s job or other legitimate income.

Another type of argument is that the cash came from transactions that have already been included in the defendant’s drug quantity. For example, if the Government can show that a defendant sold a kilo of meth for $6000.00, which adds a kilo of meth to the defendant’s drug quantity, and if the cash the Government found is $6,000.00, there would be a good argument that the cash came from the one-kilo transaction, and converting the cash into drugs would be double counting.

Conclusion.

For sentencing purposes, a defendant’s drug quantity has a huge impact on the recommended sentence range according to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which normally has a huge affect on the sentence the defendant will receive. The legal and factual issues involved in determining a defendant’s drug quantity, and in trying to reduce it, are complicated. If you or a loved one is accused of a federal drug crime in the Northern District of Texas (Dallas or Fort Worth), or the Eastern District of Texas (Sherman or Plano), you should contact John Helms an experienced federal criminal defense lawyer who has particular expertise in how the Federal Sentencing Guidelines apply in drug cases.

[1] There are two possible ways to get a sentence less than the minimum. One involves cooperation with the Government. See 18 U.S.C. §3553(e). The other involves qualifying for the “safety valve.” See 18 U.S.C. §3553(f). This article focuses only on drug quantity—not how to avoid the mandatory minimum sentence. In other articles on my website, I have written extensively on these two exceptions to a mandatory minimum sentence.

[2] See 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a)(1)(A)-(C).

source: https://johnhelms.attorney/federal-drug-cases-determining-a-defendants-drug-quantity/

Your content is great. However, if any of the content contained herein violates any rights of yours, including those of copyright, please contact us immediately by e-mail at media[@]kissrpr.com.